Projects

|

Socially Intelligent Investing

Active As a collective phenomenon, the wisdom of crowds—the tendency for the average belief in a group to be more accurate than any single group member—offers no direct benefit to individuals. Financial markets, for example, demonstrate incredible efficiency even when most individual investors make poor decisions. Popular theoretical accounts hold that individuals must remain independent to preserve collective accuracy, a requirement that prevents social learning that might benefit individuals. However, formal models of social influence predict that properly structured information exchange allows individuals to learn from each other without undermining group accuracy. We develop an experimental study in which investors make financial forecasts before and after learning the beliefs of others in a structured social network, to explore the effects of networked collective intelligence on predictive accuracy and sentiment cascades in financial markets. |

|

Dynamics of Morality & Emotion

Active We examine the direct effects of increasing the scale of social interactions (i.e., the number of different people with diverse perspectives with whom people interact) on increasing consensus in people’s beliefs about the types of virtuous behaviors. Our previous research has demonstrated that individuals vary enormously in how they classify appropriate and inappropriate behavior, yet groups of increasing size exhibit similar, replicable patterns of agreement about appropriate behavior. In this study, we generalize this principle to study the social network dynamics by which populations agree on classifying behaviors as either virtuous or not. Building on our prior results about the direct effects of social network scale on individuals’ categorical reasoning, we examine the network dynamics that lead populations of individuals who initially disagree about which behaviors are virtuous to arrive at consistent, replicable consensus in their beliefs about virtuous behavior. |

|

Vaccine Hesitancy

Active Social technologies for health have become essential means for providing underserved populations greater social connectedness and increased access to novel health information. However, these technologies have also had negative unintended consequences. Populations that have historically suffered institutional discrimination and racism offline, are now subject to implicit discrimination and further inequity as a result of online networks that shape their engagement with information about both urgent and longstanding threats to their personal health and their community’s wellbeing. Given the complex institutional and community histories that underwrite these contemporary network forces, reducing inequities requires an understanding of how to unravel the legacy of racism from emergent network patterns that, despite their unintended consequences in perpetuating health inequities, have nevertheless served a valuable role in maintaining community pride and cultural identity. The problem we are addressing is a 21st century problem that arises from the interaction between the history of institutional discrimination and racism in health, and the network dynamics of how a community’s structure affects the flow of novel information and unfamiliar ideas through a population. |

|

Content Moderation

Active The online proliferation of false, hateful, and illegal content has required social media organizations to monitor and remove content that violates their community standards – a practice known as content moderation. Despite enormous investments in online crowdsourcing, large-scale content moderation activities face a deep category problem: it is notoriously difficult for people to agree on how to categorize and manage morally controversial content. Social media organizations attempt to reduce bias in content classification by gathering the judgments of people from around the world. But these crowdsourcing efforts often require human coders to classify content in isolation, without any social interaction. Not only has this individual-level approach to crowdsourcing been found to entrench biases, but it also conflicts with the inherently social nature of how categories are defined and applied in daily life. Here, we develop a novel, network-based approach to content moderation that harnesses social processes of meaning construction to develop reliable and unbiased categories for content moderation. |

|

Civility and Democracy

Active How does the civility of online interactions affect the quality of democratic decision-making? Recent evidence suggests that incivility can increase participation, which is often thought of as desirable for good democracy. However, other research suggests that increasing incivility can reduce individuals’ ability to process information, and to reason clearly about contentious political topics. Here we use a series of online experiments with Democrats and Republicans discussing contentious political issues to determine the impact of both civility and incivility on the collective intelligence of the group’s decision. |

|

Social Origin of Inequality

Active How does social status emerge in complex societies? Why are some societies more successful in achieving social equality than others? Answering these questions involves various fields including sociology, economics, and psychology. Status is a fundamental dimension of social stratification, and it has long been a central topic in social science. As Max Weber observed, status hierarchy is sustained by widely shared beliefs that relate characteristics of people to status values. Starting with this observation, status construction theory identified certain conditions and processes of status formation. We take status construction theory one step further by investigating processes of status formation without such a precondition. We explore stability of status hierarchy by introducing fair social exchanges within a stratified population. Based on the previous works on social structures, we also investigate effects of network structure in these processes. |

|

Durable Inequality

Active Do reduced barriers to social exchange create more durable forms of inequality? We investigate this puzzle with a simple model of pairwise bargaining in populations stuck in states of inter-group inequality. This model builds on previous work suggesting populations should reach stable states of equality given infinite time. We consider the implications of both increasing the number of interacting groups, and varying the structure of interaction networks. |

|

Physician Reasoning

2023 Errors in clinical decision-making are disturbingly common. Here, we show that structured information–sharing networks among clinicians significantly reduce diagnostic errors, and improve treatment recommendations, as compared to groups of individual clinicians engaged in independent reflection. Our findings show that these improvements are not a result of simple regression to the group mean. Instead, we find that within structured information–sharing networks, the worst clinicians improved significantly while the best clinicians did not decrease in quality. These findings offer implications for the use of social network technologies to reduce diagnostic errors and improve treatment recommendations among clinicians. |

|

Race & Gender Bias in Medicine

2021 Medical decisions are based on scientific research which allows physicians to make treat patients based on probability estimates about the likelihood of diagnoses and treatment efficacy. Where medical diagnoses are made in conditions of uncertainty, physicians must rely on their judgement to generate the best decision possible. At the same time, large variations in medical procedure between geographical regions indicate that medical decisions are also subject to social influence by peers and community norms. Our pilot tests on simple estimation tasks have shown that by allowing people to share information with each other, individuals can draw on the wisdom of crowds to improve the accuracy of their beliefs. This project is designed to understand how encouraging information flow between physicians and institutions can improve the accuracy of medical diagnoses. |

|

Influencers and Optimal Seeding

2021 Despite decades of work on the network structures underlying social influence, standard measures of node centrality frequently misidentify the most influential nodes in a network. Meanwhile, these standard measures continue to be widely employed in policy-relevant domains, from marketing to public health, for the purpose of identifying influential “seed” nodes for initiating the spread of behavior. In this work, we identify a key assumption in prior network-based measures of node centrality and social distance that significantly limit their capacity to characterize social influence. Standard measures of mode centrality often assume a “simple” model of contagion, in which individuals only require exposure to one activated peer to adopt. Yet, many social contagions are “complex,” for which people require exposure to multiple activated peers. In this study, we provide novel topological measures of “complex path length” and “complex centrality”, which identify seeds that maximize the spread of social contagions. |

|

Network Dynamics of Category Emergence

2021 How do societies create shared categories? This longstanding question in social science has been approached through two dominant and competing paradigms. The first paradigm is the cognitivist approach which holds that people come to share categories because they possess innate predispositions to represent the world’s structure in similar ways. The second paradigm is the social constructivist approach which holds that people construct meaning dynamically in social networks, where interaction can lead to radically different category systems across societies. The social construction account is consistent with recent experiments which contend that communication in dyads and small social groups can amplify individual variation, leading separate communities to converge on dissimilar representations of the same stimuli. However, recent formal models illustrate that agents with minimal biological constraints can converge on similar categories when interacting in social networks. In this study, we use formal models and online experiments to challenge both of these paradigms in accounting for how categories emerge in social networks. Specifically, we develop novel theories and analyses to explain how categories emerge in social networks of various sizes and topologies. |

|

Networked Innovation

2020 Do efficient communication networks increase innovation? Scientists, engineers and strategists all work within highly connected environments where each person’s solutions are used to inspire and inform the work of others. The communication networks between researchers can determine the rate at which new ideas and innovations reach the rest of the community, giving rise to better solutions to difficult problems. As the complexity of the problem increases, so does the putative need for more efficient collaboration networks. |

|

Networked Smoking Cessation

2020 Can social influence reduce bias in the interpretation of scientific information, even when this information challenges people to change negative health behaviors? Smokers often misinterpret the scientific information in anti-smoking warning labels because of motivated reasoning, where people misconstrue data on the basis of political and psychological biases. The addictiveness of cigarettes creates an even stronger incentive for smokers to ignore or misinterpret the scientific information in anti-smoking campaigns. In an online experiment, we use engineered social networks to harness peer influence among smokers and nonsmokers in such a way that counteracts and eliminates biased interpretations of warning labels. The methods developed for this study are relevant more broadly to the design of communication networks that can resist the rise of misinformation, while also fostering the growth of positive health behaviors. |

|

Wisdom of Partisan Crowds

2019 Normative theories of deliberative democracy are based on the premise that social information processing can improve group beliefs. Research on the “wisdom of crowds” has found that information exchange can increase belief accuracy in many cases, but theories of political polarization imply that groups will become more extreme—and less accurate—when beliefs are motivated by partisan political bias. While this risk is not expected to emerge in politically heterogeneous networks, homogeneous social networks are expected to amplify partisan bias when people communicate only with members of their own political party. However, we find that the wisdom of crowds is robust to partisan bias. Social influence not only increases accuracy but decreases polarization without between-group network ties. |

|

Birth Control Connect

2019 This project evaluates women’s attitudes about birth control. We conduct a randomized controlled trial to examine whether anonymous online discussion with women who use intrauterine devices (IUDs) as their method of birth control can change the attitudes toward IUDs among women who have never used IUDs. The intervention is an anonymous online community, in which non-IUD users are assigned either into 9-person groups with other non-IUD users or 9-person groups with 4 IUD users. The study will observe attitude changes among non-IUD users within these groups. |

| Communicating Climate Change

2018 Can social influence reduce bias in the interpretation of scientific information? Vital science communications are frequently misinterpreted as a result of motivated reasoning, where people misconstrue data on the basis of political and psychological biases. In the case of climate change, studies show that conservatives are much more likely than liberals to inaccurately judge climate data. In this study, we provide a method for facilitating cross-party communication that eliminates biased interpretations of climate data among conservatives, while also improving the interpretations of liberals. In an online experiment, we placed conservatives and liberals in decentralized networks where they exchanged information while interpreting climate data. We find that networked peer influence drastically improves the accuracy of interpretations among both conservatives and liberals, compared to control subjects who interpreted the same data on their own. |

|

|

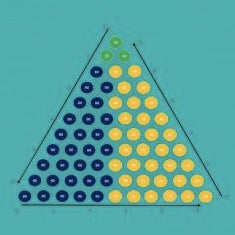

Creating Critical Mass

2018 The “tipping point” is a common explanation for sudden shifts in collective behavior, but the limitations of historical evidence and conflicting theoretical models present a challenge to understanding how a small but committed group can change the behavior of an entire population. On the one hand, economic theories emphasize strategic choice and suggest that established conventions are highly stable. On the other hand, a popular physics model emphasizes the dynamics of individual interactions, predicting that a group with just 10% of the population can initiate social change, but does not for account individual preferences to conform to the majority. |

|

Preventing Cervical Cancer With Twitter

2018 This project studies the discussion of HPV vaccination and cervical cancer on social media. Cervical cancer causes 4,220 annual deaths. 17% women do not receive appropriate Pap smear screening. Only 35% of girls 13 to 17 fully receive HPV vaccine. Unfortunately physician based recommendation approaches miss many women. However, social media is used extensively – especially by young women. Using a mixed methods approach combining machine learning, qualitative analysis, and experimental manipulations. We will analyze Twitter discussion to determine how social media messages can most effectively be used to promote HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screenings. |

|

Collective Intelligence

2017 Decentralized networks offer enormous potential for crowd-sourced information aggregation, whether it takes the form of emergent market forces or a deliberative organizational process. In 1907, Sir Francis Galton observed that a large number of individual beliefs can produce highly accurate opinions when averaged. Even when no one person knows the right solution, independent errors cancel each other out, and groups as a whole can produce answers with pinpoint accuracy. The challenge with harnessing such statistical power is that when people communicate, they learn from each other, and in turn adjust their beliefs based on information circulating in the network. |

| Support or Competition?

2016 Online social networks have become a highly attractive target for large scale health initiatives; however, there is insufficient knowledge about why online networks might be effective sources of social influence for improving physical activity levels. In a randomized controlled trial, we evaluate the effects of social support and social comparison independently, and in combination, to determine how social motivations for behavior change directly impact people’s exercise activity. |

|

|

Origins of Networks

2015 Recent research on social contagion has demonstrated significant effects of network topology on the dynamics of diffusion. However, network topologies are not given a priori. Rather, they are patterns of relations that emerge from individual and structural features of society, such as population composition, group heterogeneity, homophily, and social consolidation. |

|

Shape UP

2015 Sedentary lifestyle is an escalating national and global epidemic that has commanded increasing attention from health care professionals and social scientists. Paradoxically, the advent of the Internet and social media may be both an explanatory factor in this epidemic, and a potential solution. |

|

Emergence of Social Norms

2015 How do norms emerge? In small groups, people have complete knowledge of one another’s behaviors, making it relatively easy to create shared expectations. In larger groups, reaching a consensus or convention on basic behaviors such as how to greet one another, which side of the road to drive on, and what constitutes a “fair” bargaining outcome, can be established by top down, authoritative decree. However, most examples of large-scale patterns of social coordination do not rely upon global control, nor can they always assume common knowledge among all members of a group, or pre-existing cultural “focal points” that will provide familiar references for social self-organization. |

|

Network Evolution

2013 How do online health networks evolve? A growing number of online health communities offer individuals the opportunity to receive information, advice, and support from their peers. Our recent studies have demonstrated that these new online contacts can be important informational resources, and can even exert significant influence on individuals’ behavior in various contexts. However little is known about how people select their health contacts in these virtual domains. This is because selection preferences in peer networks are notoriously difficult to detect. In existing networks, unobserved pressures on tie formation—such as common organizational memberships, introductions by friends of friends, or limitations on accessibility—may mistakenly be interpreted as individual preferences for interacting/not interacting with others. |

|

Stability in Critical Mass Dynamics

2013 Collective behaviors often spread via the self-reinforcing dynamics of critical mass. In collective behaviors with strongly self-reinforcing dynamics, incentives to participate increase with the number of participants, such that incentives are highest when the full population has adopted the behavior. By contrast, when collective behaviors have weakly self-reinforcing dynamics, incentives to participate “peak out” early, leaving a residual fraction of non-participants. In systems of collective action, this residual fraction constitutes free riders, who enjoy the collective good without contributing anything themselves. |

|

Homophily, Networks, & Critical Mass

2013 Formal theories of collective action face the problem that in large groups a single actor makes such a small impact on the collective good that cooperation is irrational. Critical mass theorists argue that this ‘large group problem’ can be solved by an initial critical mass of contributors, whose efforts can produce a ‘bandwagon’ effect, making cooperation rational for the remaining members of the population. |

|

Diffusing Health Innovations

2011 How does the composition of a population affect the adoption of health behaviors and innovations? To understand how changes in people’s social “neighborhoods” affect the spread of health innovations, we developed an in vivo study that manipulated the level of “homophily”—similarity of social contacts—among the participants in an online fitness program. |

|

Scale Free Failure

2009 A class of inhomogenously wired networks called “scale-free” networks have been shown to be more robust against failure than more homogenously connected exponential networks. However, for “complex contagions,” such as social movements, collective behaviors, and cultural and social norms, multiple reinforcing ties are needed to support the spread of a behavior diffusion. Scale-free networks are much less robust than exponential networks for the spread of complex contagions, which highlights the value of more homogenously distributed social networks for the robust transmission of collective behavior. |

|

Spreading Behavior Online

2009 How do behaviors spread through social networks? Harnessing the new opportunity offered by social media, our research pioneered the use of online technologies to investigate the effects of social structure on the spread of health behaviors. Using experimentally controlled online health communities, we recruited over 1,500 people to join a health website, called “The Healthy Lifestyle Network,” in which participants were embedded into anonymous, Internet-based networks. Once participants joined the study, they were randomized into one of two network conditions – one community was designed with tightly clustered, “strong tie” networks, and one was designed with randomly structured “weak tie” or “small world” networks. |

|

Complex Contagions

2007 The strength of weak ties is that they tend to be long—they connect socially distant locations, allowing information to diffuse rapidly. The authors test whether this “strength of weak ties” generalizes from simple to complex contagions. Complex contagions require social affirmation from multiple sources. Results show that as adoption thresholds increase, long ties can impede diffusion. |

|

Cultural Drift

2007 Studies of cultural differentiation have shown that social mechanisms that normally lead to cultural convergence—homophily and influence—can also explain how distinct cultural groups can form. However, this emergent cultural diversity has proven to be unstable in the face of cultural drift—small errors or innovations that allow cultures to change from within. |

|

The Emperor’s Dilemma

2005 The authors demonstrate the uses of agent-based computational models in an application to a social enigma they call the “emperor’s dilemma,” based on the Hans Christian Andersen fable. In this model, agents must decide whether to comply with and enforce a norm that is supported by a few fanatics and opposed by the vast majority. They find that cascades of self-reinforcing support for a highly unpopular norm cannot occur in a fully connected social network. |